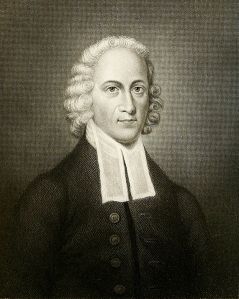

Jonathan Edwards is almost certainly America’s best theologian. Edwards lived in Northampton, Massachusetts in the 18th century and was a part of the Reformed tradition and the Puritan heritage. He was a pastor. He was a preacher. He was a verifiable genius. He was part of a revival that is now called the Great Awakening.

As a follow up to my last post, I want to point to Edwards as being a unifying theological force in this discussion/debate between continuationism and cessationism (see previous post for definitions of these words). Edwards was a cessationist. He preached that the extraordinary gifts of the Spirit ceased at the end of the apostolic age of the church.

But it is my belief that Edwards provides warnings and cautions to both continuationists and cessationists. For continuationists, Edwards warns us not to put too much stock in our personal spiritual experience. In his classic work The Religious Affections Edwards cautions that enthusiastic experiences cannot provide the basis for our relationship with God – true religion is a matter of the heart (the affections – motives and desires) and so experiences do not guarantee true religion. So we should be cautions of experience and the subjective.

And at the same time since Edwards prioritized the affections, he believed strongly in the life-giving, vital and dynamic power of the Holy Spirit in the life of the believer! Regarding his own intimate experience of the presence of God, Edwards wrote:

Now, if such things are enthusiasm, and the fruits of a distempered

brain, let my brain be evermore possessed of that happy distemper!

If this be distraction, I pray God that the world of mankind may be

all seized with this benign, meek, beneficent, glorious distraction.[1]

In other words, while we should not put too much stock in our experiences of the Holy Spirit, it is really important that as Christians we have a strong and healthy experience of the presence of God in a way that our affections are set ablaze. This is a correction to some charismatic tendencies where (perhaps) the subjective aspects of the faith are prioritized, and it is also a correction to cessationist tendencies where (perhaps) the rational aspects of the faith are emphasized. In conclusion, cessationists and continuationists, read more Edwards!

[1] Jonathan Edwards, “Some Thoughts Concerning the Revival,” in The Great Awakening, vol. 4 of Works of Jonathan Edwards, ed. C. C. Goen (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1972), 341.